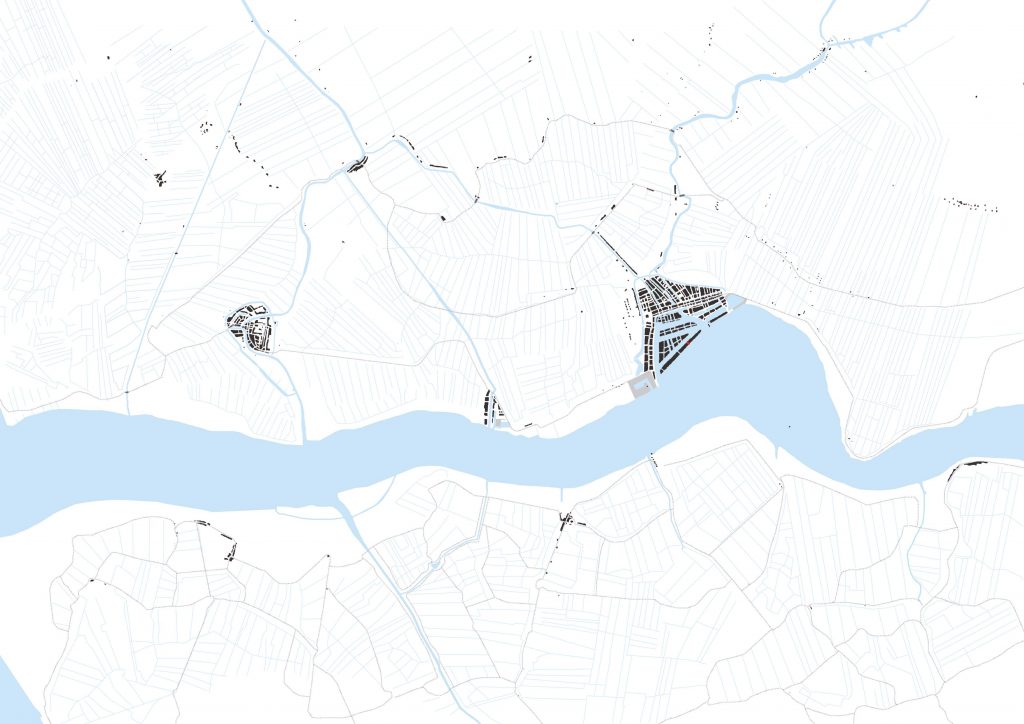

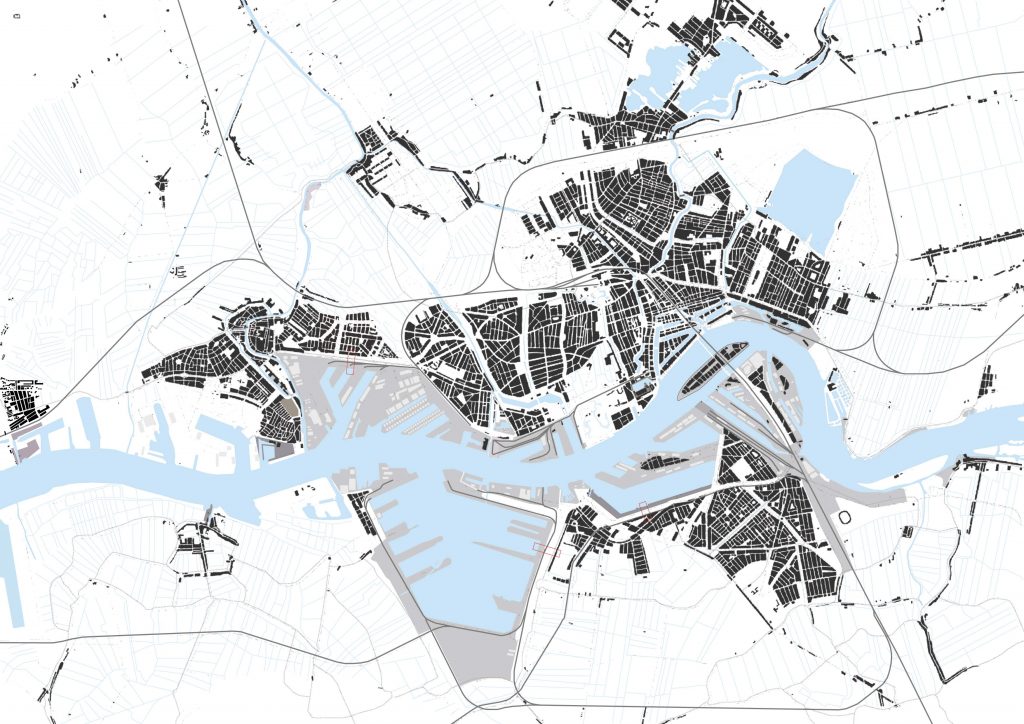

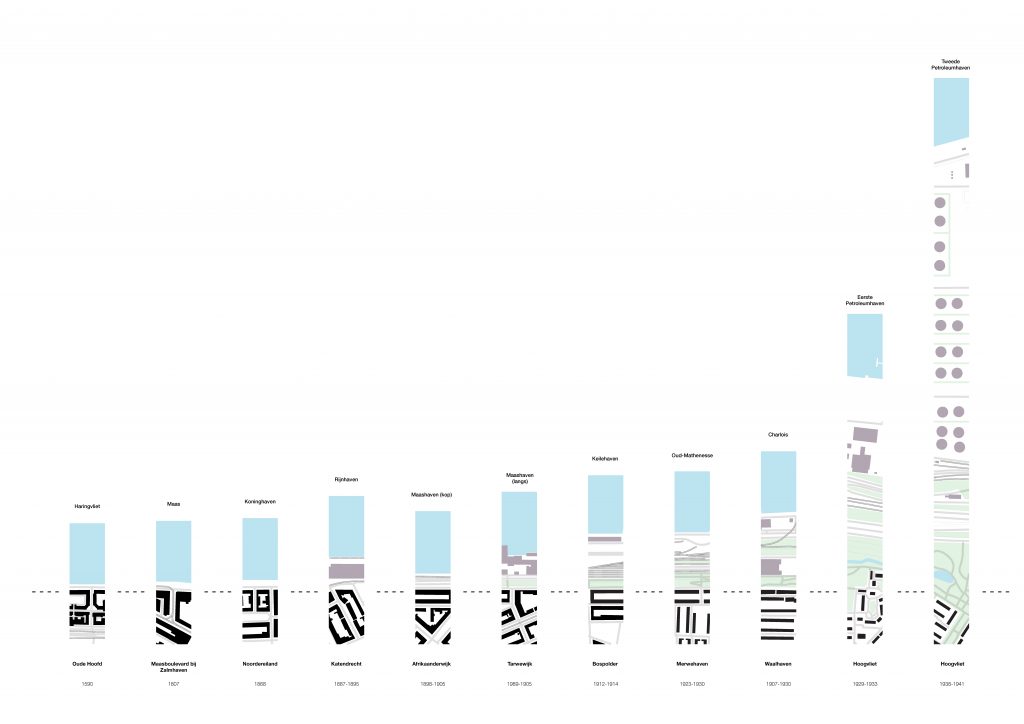

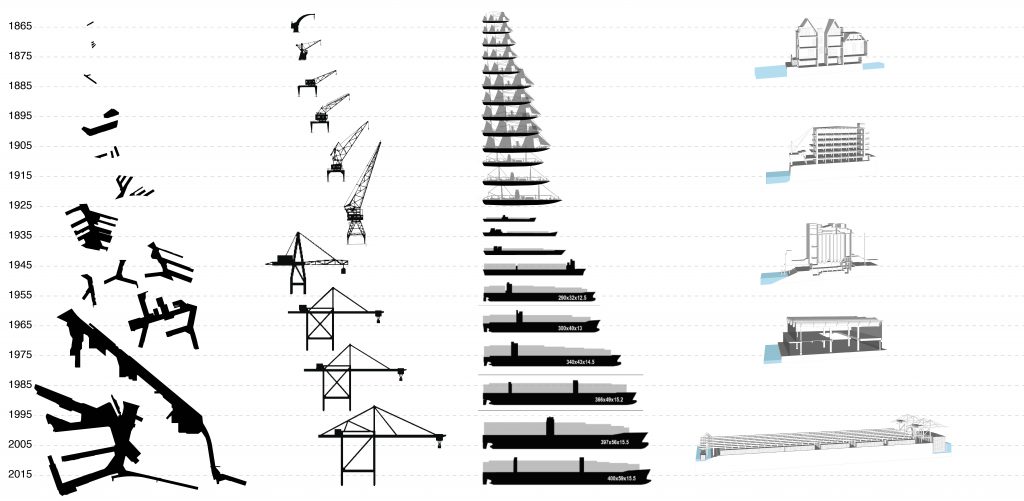

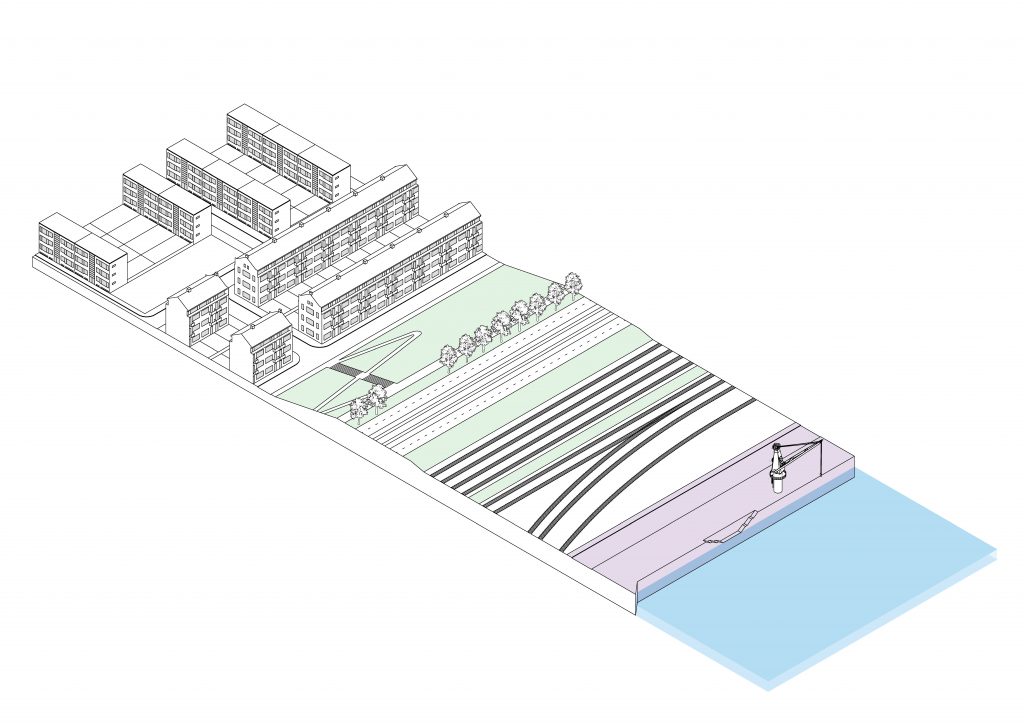

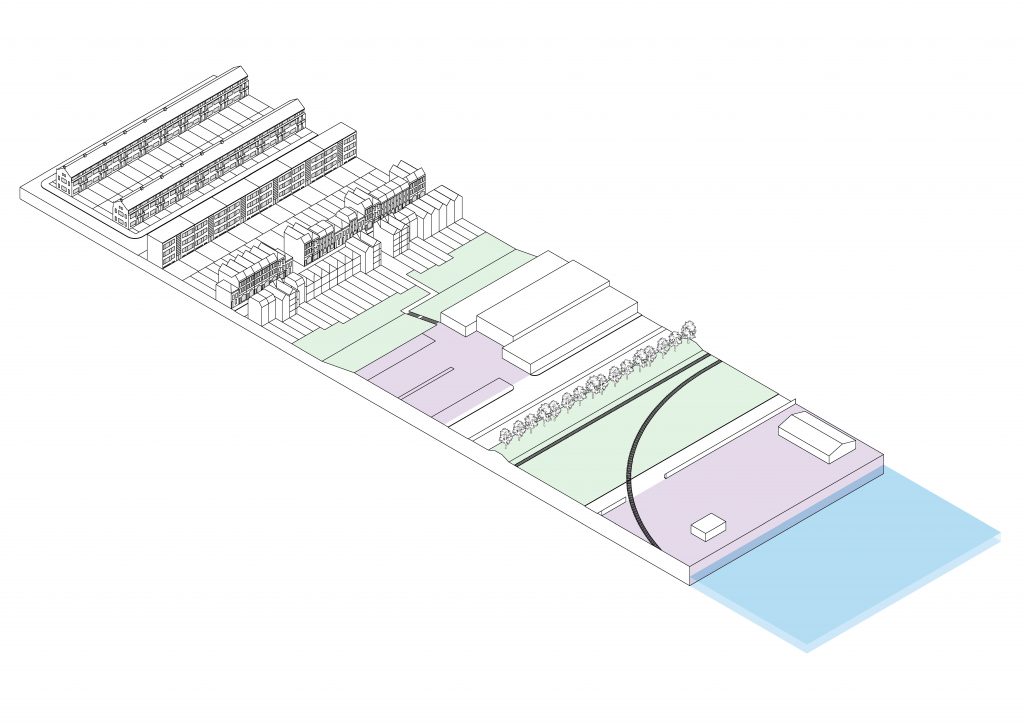

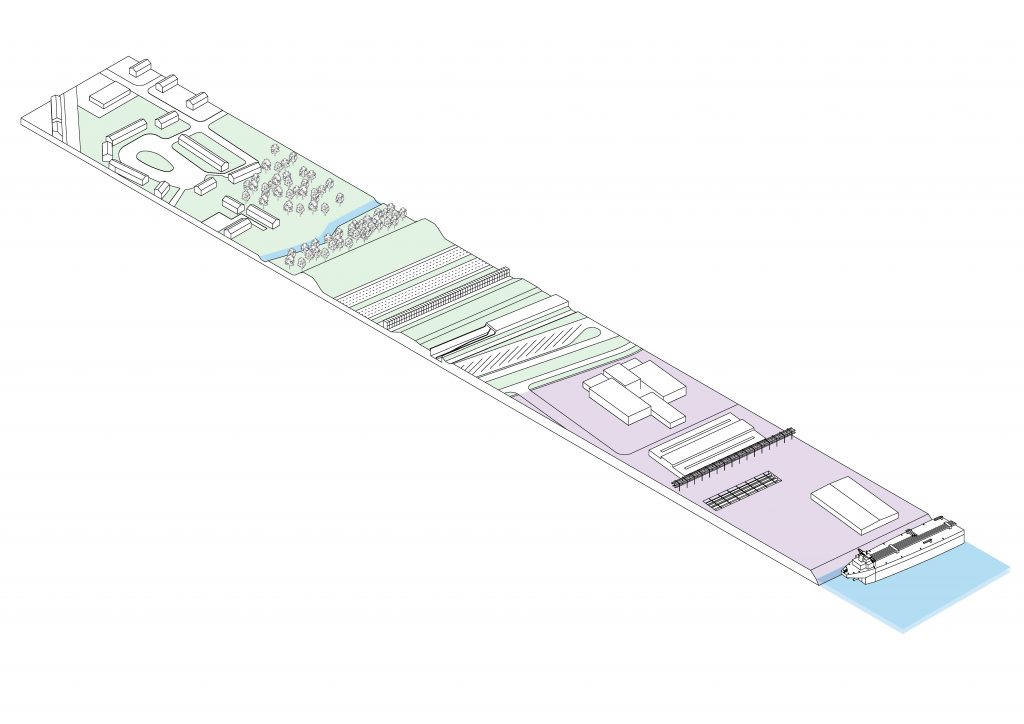

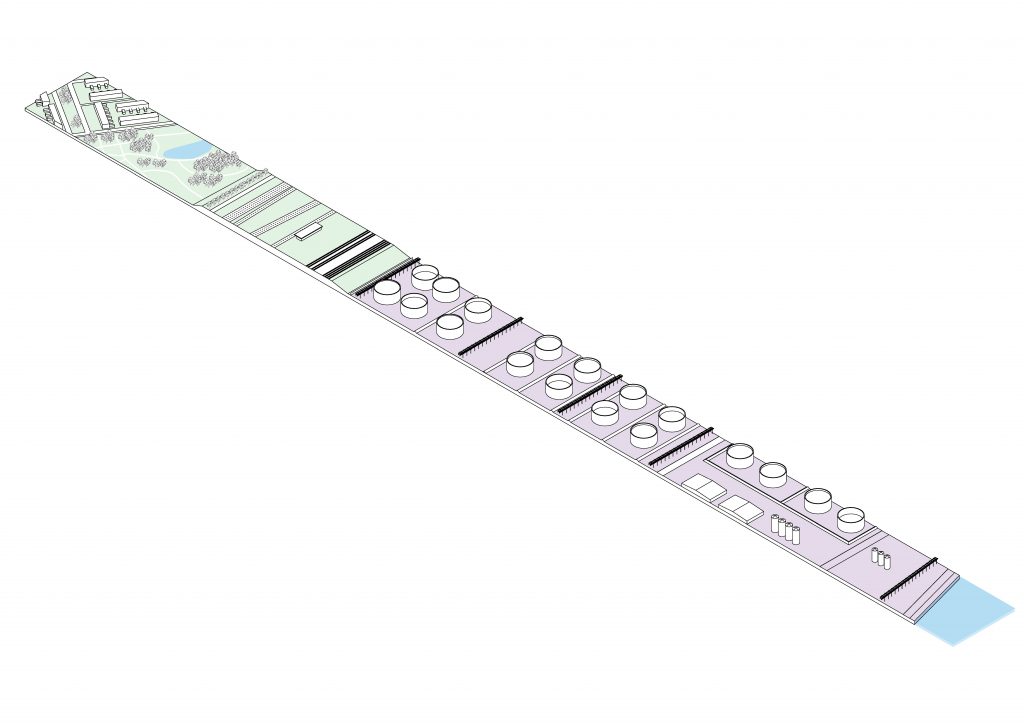

Rotterdam, city with the biggest port of Europe. Much has been written on the urbanism of Rotterdam in relation to this giant port, by Umberto Barbieri, Frits Palmboom, Michelle Provoost and Paul van de Laar to name a few. This research proposes a synthisizing and graphic view of Rotterdam and its port.

This series of graphics is a reduced version of a research on the theme of program in the urban realm, conducted in the graduation studio The Intermediate Size, authored by Justin Agyin, Lennart Arpots, Joep Coenen and Kenzo Lam.